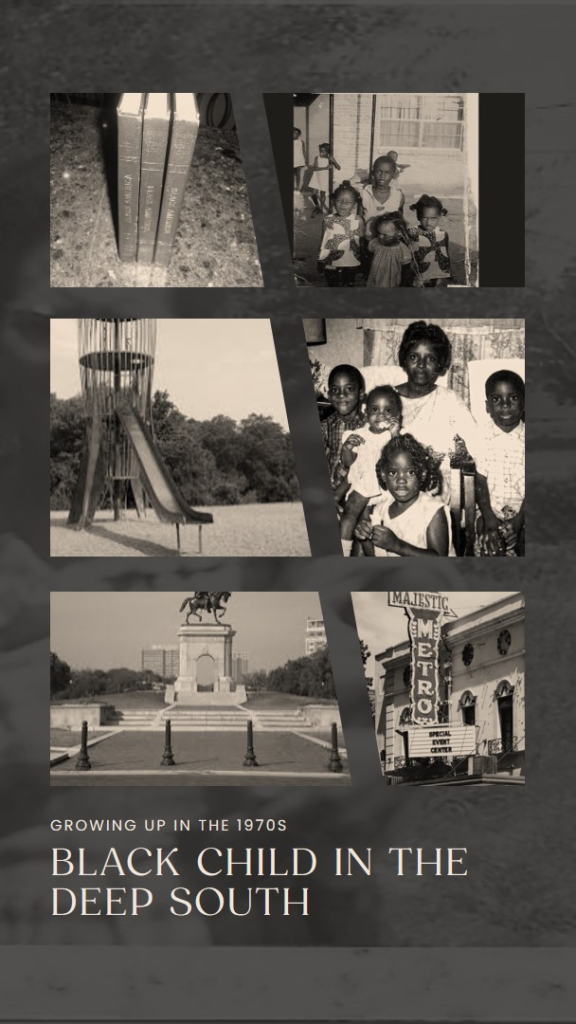

Growing up as a “Black Child” in the “Deep South” in the 1970s and raised to become an “American”

K Tyler

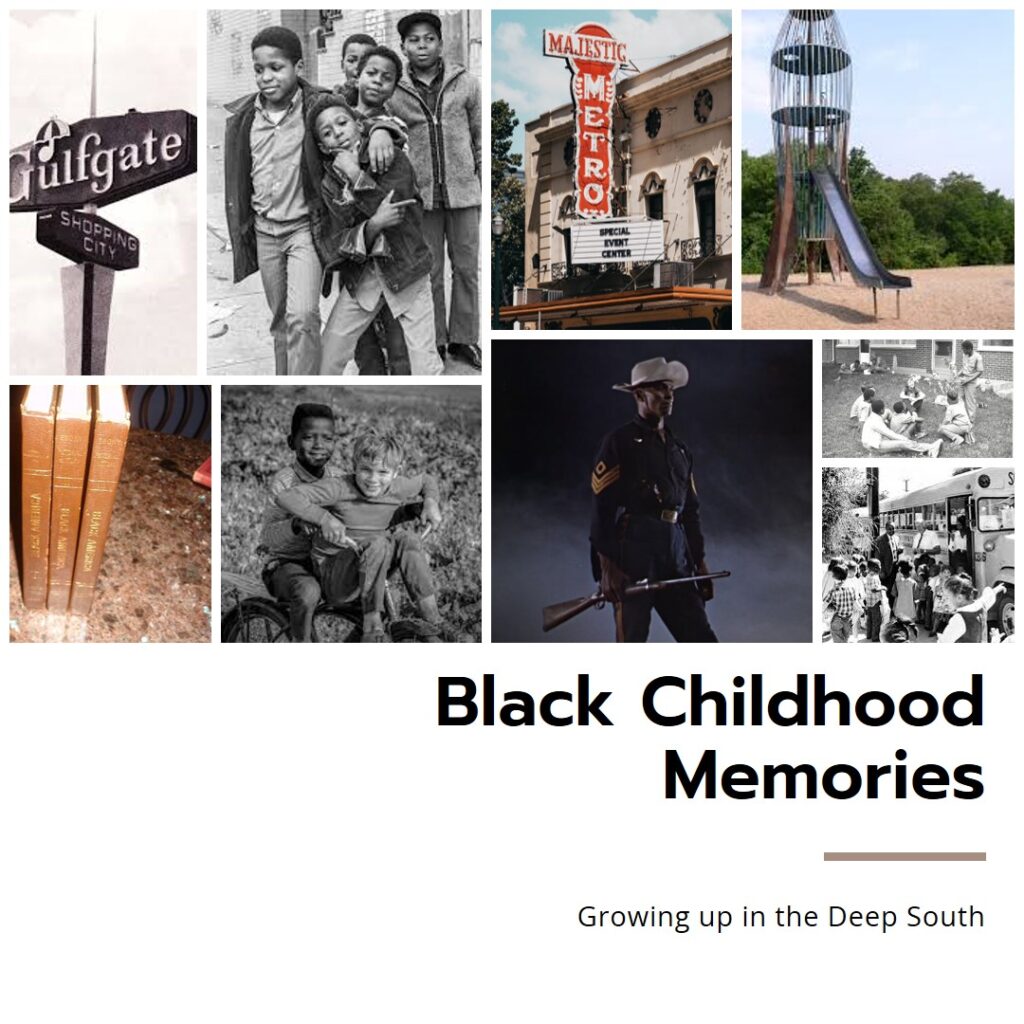

Growing up Black in the 1970s Deep South meant facing segregation and discrimination daily. This shared history taught us resilience and determination in a society that often pushed us aside. Although schools were desegregated, unequal education persisted. Many Black children learned to be cautious, work hard, and navigate around the police. What did growing up Black in the 1970s teach me? Strength and persistence are crucial when faced with adversity.

Growing up as a Black child in the Deep South in the 1970s presented numerous challenges and experiences, including navigating segregation, discrimination, and racial tension. This is your father's history, your Homie's history, your Mama Bear's history, your Meemaw's history, your Cuz's history, your Parental Unit's history, and your Brother from Another Mother's history. These experiences shaped not only one's understanding of race and identity but also their resilience and determination to thrive in a society that often marginalized them. Despite the 1970s desegregation of schools and cinema theaters in the Deep South, other issues persisted for black children, such as educational institutions. According to some, the relationships between Black and white students in desegregated institutions improved. Conversely, a child who visited Mississippi in the 1970s was astounded by the segregation he observed, which included movie theaters with balconies reserved for Black patrons and separate water fountains and restrooms.

In the 1970s, some movie theaters integrated, while others maintained separate balcony sections for Black patrons. To prevent integration, many publicly owned swimming pools remained closed or sold. Some Black children in the Deep South might also have faced advice to avoid prolonged sun exposure, refrain from retaliating, or avoid driving in front of police. Additionally, their race may have required them to labor twice as hard. What did growing up as a Black child in the Deep South in the 1970s teach me about what it means to be an American? In the end, these difficulties and experiences had a big impact on my personality and view of the world, showing how important it is to be strong and persistent when things go wrong. Through looking at these formative years, we can learn more about how race, region, and identity affect a person's journey to fit in with American culture.

Changes in my family were especially noticeable between 1955 and 1965. Many of my parents’ relatives migrated to the West in search of better opportunities. My family and I had just started out when my parents made the big move from St. Landry Parish, Louisiana, to Beaumont, Texas. My parents brought a horde of cousins, aunts, uncles, and other relatives with them. My relatives ultimately settled in Houston, Texas, and then in California. The migration westward brought about new challenges and opportunities for my family as we navigated a different environment and culture.

Despite the distance from our Louisiana roots, the sense of community and connection to our heritage remained strong throughout the generations. As we adapted to our new surroundings, we found support and camaraderie within the tight-knit community of fellow Louisiana transplants. Our shared experiences and traditions helped us preserve our cultural identity even as we embraced the opportunities that came with our westward migration.

Between 1910 and 1970, 6 million African Americans left the rural South for the urban Northeast, Midwest, and West due to poverty and Jim Crow-era racial segregation. Five million black southerners traveled north and west between 1915 and 1960. Most migrants relocated to northern cities, including Chicago, Detroit, Pittsburgh, and New York. Many moved west after WWII to Houston, Dallas, Los Angeles, Oakland, San Francisco, Portland, and Seattle (staff). We were family, regardless of how far apart we were geographically. We devised means of communication.

As a child, I recall growing up in the Deep South, which encompassed Texas and Louisiana and was home to our family’s illustrious culinary legacy. I recall certain aunts and uncles claiming to have “family secret” recipes that they passed on to their children and their children’s children. These recipes were more than just food; they were a way for us to stay connected to our roots and traditions despite the physical distance between us. The act of cooking these dishes became a form of communication that transcended geographical boundaries, keeping our family bond strong no matter where we were located.

During the 60 years from 1910 to 1970, 6 million African Americans fled the rural South. They did this to escape poverty. They also wanted to flee the oppressive racial segregation of the Jim Crow era. Between 1915 and 1960, 5 million southerners moved north and west. Most settled in cities. Chicago, Detroit, Pittsburgh, and New York were the first stops for many. But, after World War II, these pioneers pushed farther west. They settled in cities like Houston and Dallas. They also settled in Los Angeles, Oakland, and San Francisco. They also settled in Portland and Seattle.

(staff).

We frequently participate in family activities that are just beginning to gain popularity in the culinary world. For instance, restaurant menus have rapidly expanded to include sweet potato fries, a product that has been commercially available for a few years. My late stepfather, Troy “Trey” Joseph, had been serving us sweet potato fries since we were small children. He would always say that it was a tradition passed down from his own parents, who were known for their innovative approach to Southern cooking. The unique blend of sweet and savory flavors in the sweet potato fries quickly became a beloved staple at our family gatherings. Troy’s recipe for sweet potato fries was a hit with everyone who tried them, and we always looked forward to enjoying them together.

The tradition of making and sharing sweet potato fries continues to this day, keeping his memory alive in our hearts and taste buds. I can proudly boast that my family produced numerous cooks and bakers who became local celebrities in their own hometowns. As a child, I recall seeing “black business” in action firsthand through my aunts and uncles, who were entrepreneurs who operated restaurants,car repair shops, highway and street construction companies, and catering establishments. When I was a child, I had no idea how important my family was to the world in which I grew up.

When I was growing up in the 1960s and 1970s, everything was black and white. I have no knowledge of Jim Crowe-era artifacts like “colored only” drinking fountains or “colored only” facilities, but I do recall family unity. I started the “head start” program in Opelousas, Louisiana, in 1966, and my class, as far as I recall, contained both white and Black students. This experience taught me the importance of diversity and inclusion from a young age, shaping my perspective on the world. Despite the racial tensions of the time, I was fortunate to live in a welcoming community that valued education and unity.

My best friends in the world, apart from my brother and cousins, were a little girl named Laura (Lola) and her little brother, Frank Boyer, in the wonderful state of Louisiana. Together, we were always causing mischief wherever we went. In fact, we were known as the “troublemakers” of the neighborhood. We were always playing together and going on the most amazing adventures. I really think we bonded more as a support group protecting ourselves from the local bully named Hilton. He was really a good man as he grew older but as a child he was horrible. We played at their house and at my grandma’s house without any problems or undesirable occurrences. Frank and his sister were “white,” but we never saw “color” as children—only the possibilities of friendship and fun.

Frank’s father, a Marine veteran with numerous decorations, remains etched in my memory. To me, his best quality, along with that of his wife, was his attitude towards us as children. He didn’t see us as black; he saw us simply as kids. Frank’s parents treated us with kindness and respect, which made a lasting impact on me as I grew older. Their example taught me the importance of seeing beyond race and treating everyone equally. Frank’s dad was part of that “great generation” that fought and sacrificed for our country during World War II. It was Frank’s dad who held me to my conviction of serving my country with honor.

This example highlights how Frank’s father’s attitude of treating everyone equally, regardless of race, influenced me as I grew older. It also demonstrates the positive impact that a role model like Frank’s father had on shaping my values and sense of duty towards serving my country. Frank eventually became a commissioned officer in the Louisiana National Guard and served in Desert Storm with outstanding distinction; he also commanded a unit during the Hurricane Katrina disaster in New Orleans. Frank’s father’s character and values, regardless of race, influenced me as I grew older.

In the summer of 1965, half a million disadvantaged children between the ages of 3 and 7 helped the federal government test a promising idea in the war against poverty: that children who lacked the basic medical, emotional, nutritional, or educational attention needed to perform well in school would benefit from a comprehensive preschool experience that combined these elements.

(“Elementary and Secondary Education Act”)

I was enrolled in the head start program by my maternal grandmother when I was six years old. My mother was attending college in Florida at the time. In southern schools, it was customary for students whose birthdays fell after the start of the school year to be required to begin the following school year. I was born in September, and September marks the start of the academic year. This was my “first strike” in life, and I was too young to comprehend the consequences of starting school a year later. When I thought about the theatrical production of the film “Soul Food,” I noticed a similarity with our family, albeit on a lesser scale.

I recall dividing factors in Opelousas, Louisiana such as the “north” park being reserved for whites only and the “south” park being open to everyone else. Simultaneously, I recall visiting both parks without encountering any difficulties. Our family traveled constantly throughout my life. The majority of our travel was spent visiting relatives, although we were a unique breed of Texans. We adored the outdoors, and everything associated with it. When not visiting relatives, traveling was for fishing, hunting, or camping. You must keep in mind that we are discussing the mid-1960s and early 1970s, a vital period in the development of black children in the South. During this time, segregation was still prevalent in many parts of the South, making it challenging for black families to access certain spaces.

I recall being stationed at Fort Polk. Louisiana in 1983 and being surrounded by two sundown towns, Anacoco in the Northwest, and Pitkin in the Southeast. Fort Polk is now Fort Johnson after the US Army moved to honor a World War I hero. African American soldier. Sgt. William Henry Johnson, who was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor in 2015, In a cautionary note, a CNN reference states that it was part of an effort to strip Confederate leaders of the honor. (Iyer) However, I believe with all my heart that this renaming reflects a shift towards inclusivity and recognition of the contributions of African American soldiers. It serves as a reminder of the ongoing efforts to dismantle systemic racism and promote equality in all aspects of society. During formations, we were briefed regularly to avoid those areas.

The racial tensions and segregation that persisted in the South during this period greatly impacted the daily lives and movements of Black, Hispanic, and Asian families. It was a time when even military personnel had to be cautious and aware of their surroundings due to the prevalence of sundown towns in certain areas. Pitkin was my immediate concern because I had to pass through Pitkin when I visited relatives in Opelousas, Washington, or Port Barre, Louisiana. There’s more to a sundown town than just being a racist spot. A whole neighborhood, or even a county, was purposely “all white” for many years. “All white” is in quotes because some towns kicked out all but one black family but let one stay.

Despite these challenges, my family made a conscious effort to expose me to diverse environments and experiences, which shaped my perspective on race and identity. Growing up in Texas and having family in Louisiana made for a fascinating childhood for me. We visited local relatives or friends at least four to six times per week, and we took two to three trips per month outside of the city and state. I never realized until now how frequently we traveled between Houston and Beaumont, Texas, and Opelousas, Washington, and Port Barre, Louisiana. Back then, this was known as “making the run.” It started with our parents and ended with us as young adults, making the same run in the mid-1980s.

During this time period, our crew consisted of myself, my brother Craig Tyler, and my cousin Tony Allen. We were inseparable during our weekly trips back and forth. People in Louisiana referred to us as “them Texas boys,” suggesting that we were untouchable. Before Interstate 10, “I-10” became known for more than the drug trafficking highway; it was our lane. Whether traveling Highway 90 or Interstate 10, we always journeyed together as a family. This was when less than $20 could fill up your car’s fuel tank with no problem. With that being said, this was my version of the “good old days.” Later, I took a road trip with my younger brother, David Joseph, and it was fantastic because it was the first time we had interacted as adults. We had a wonderful time driving from Houston to Columbus, Ohio, and I introduced him to the “white-castle burger.” This is the period of my life when I discovered who my brother was.

My favorite Westerns and war movies starring John Wayne, Woody Strode, or Clint Eastwood made me realize how inextricably linked my future would be to these actors. John Wayne’s five-decade career in Hollywood made him a symbol of American masculinity and patriotism. Wayne is best known for his westerns, but he also directed a dozen films about World War II in the two decades following the United States’ entry into the conflict in December 1941.

As a young man, I felt a sense of duty and patriotism, and I wanted to continue the legacy of my ancestors, who participated in every war the United States has ever faced. My grandfather served in World War II, and I had uncles and other relatives who served in the Korean and Vietnam wars. I joined the military before I was old enough to do so. During active duty, I would take leave and travel to great destinations, which, of course, set me up for the future because these trips gave me the confidence to travel alone to any location in the world that I desired. My travels began when I joined the military, where I was exposed to over fifteen nations over the course of my military career.

I particularly enjoyed going to the warmer climes of Southern Asia, and I have had numerous adventures all around the Philippines’ island nation. However, as a second-generation military person, I have always harbored an ardent desire to visit Vietnam. During my childhood in the 1960s and 1970s, Vietnam consistently featured on all television channels and in most of the movies I watched.

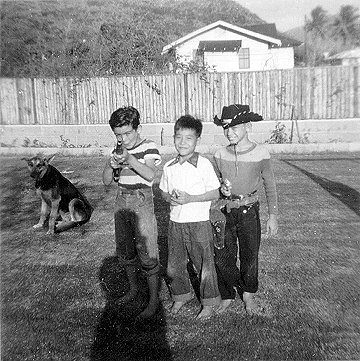

At this point in my life, all of my ethnic “perceptions” have come through modern entertainment in the form of movies and television shows. Ethnic perceptions are a part of ethnic identity, which is a person’s sense of belonging to an ethnic group based on their cultural heritage, values, traditions, and other factors. (“Ethnic Identity: The Domain of Perceptions of and Attachment to Ethnic Groups and Cultures on JSTOR”) As children, we lived in the moment and made the most of every day and night. In Houston, as we did in Beaumont, Texas, we used to venture into the woods and create trails where none existed. We were the neighborhood explorers, and we did nothing but explore. We traveled so frequently that our house appeared vacant to our neighbors, attracting neighborhood criminals to attempt “breaking in.” However, in our area, we had unity, as two out of every three households had direct connections to Louisiana, which served as an informal neighborhood watch.

We felt safe knowing that each house was looking out for one another. Even though we were just kids, we knew that our unity and sense of community were stronger than any criminal activity that could come our way. Our adventures in the woods were filled with laughter, discovery, and a sense of camaraderie that bonded us together as neighborhood explorers and neighbors. It was a time of innocence and freedom, which we will always cherish and look back on with fond memories. Again, I use this reference to “the good old days.” It was truly a different time, a safer time, a less political time. The elderly served as patriarchs and matriarchs in our family, as they do in many others throughout Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean. We resolved internal conflicts within the family. In my youth, I had no recollection of family reunions.

This was due to the fact that our activities centered around house improvements, barbecues, gumbos, hog butchering (crackling), and fishing. We referred to these activities as “gatherings” or “get-togethers.” Our family was strong because our elders were so influential, so I never saw or needed to know these things as a child. Naturally, this has altered over time. In recent years, we have relegated ourselves to meeting mostly during funerals and birthdays, having evolved from get-togethers to family reunions. And now that the pandemic has entered its fourth full year, even funerals and weddings are experiencing a decline in attendance. Two years ago, video marriages, video funerals, and video church were a modest component of the participation system; however, video has already supplanted formal interaction for employment, religion, recreation, and memorials. Virtual events and gatherings are becoming increasingly common as technology continues to advance. This shift has not only changed the way we connect with others but also how we honor and remember our loved ones.

There was one movie that brought to mind my thoughts of being an American versus an African American. I feel that, above all, “since this is the land of my father and my father’s father, I am automatically entitled as a citizen to the title of American.” There is only one reference I can remember from a movie entitled “Major Dundee.” In this film, a character states, “You’re an American. We’re all Americans.” This quote resonates with me as it highlights the idea of unity and shared identity within the diverse fabric of American society. (“Major Dundee”)

Major Dundee is a 1965 Western film directed by Sam Peckinpah and starring Charlton Heston, Richard Harris, Jim Hutton, and James Coburn.

Plot: Dundee seizes the opportunity for glory, raising his own private army of Union troops (black and white), Confederate prisoners led by his former friend and rival from their days at West Point, Captain Tyreen (Richard Harris) a few Indian scouts, and a gang of civilian mercenaries to illegally pursue Charriba into Mexico. When the diverse factions of Dundee’s force are not fighting each other, they engage the Apaches in three bloody battles. At the end of the campaign, as Dundee’s force heads home as one, as Americans, the narration notes that it's now April 16, 1865, and the soldiers are still unaware that the Civil War is over, and President Lincoln has been assassinated. That’s the way I feel as an American. The film ends with Dundee and his men returning to a changed America, symbolizing the tumultuous period of post-Civil War reconstruction. The juxtaposition of their ignorance of national events highlights the disconnect between individual experiences and a broader historical context. (“Major Dundee”)

I do not remember encountering the term “African American” until the 1990s, following the events of the Desert Storm operation. Before that, people commonly used the term “Black” or “negro.” The shift towards using “African American” was seen as a way to emphasize the cultural heritage and roots of black Americans, acknowledging their connection to Africa. This change in terminology reflected a broader societal acknowledgment of the importance of identity and representation within the black community. When I traveled overseas, people did not refer to me as an African American, Negro, or Black, but rather as a man, a young man, an American, or Kenneth. This prompts me to recount my initial journeys to Europe. When we arrive at the airport, a group of people greets us and immediately puts us at ease. Even getting through immigration is taking us longer now, and this is just the beginning. People may want to photograph you simply because you are Black in certain parts of the world. People may assume you are an athlete, a drug dealer, or a prostitute solely based on your race. They may wonder where you are from and incorrectly assume you are “African.”

When was an ethnic term ever used to denote a man’s character or content? I did not identify as African; I was not your black man, nor was I a negro, as my birth certificate claimed. My daughter April Tyler’s birth certificate lists “Black” as her race. As I think about how social labels and ideas about who we are can change our lives, I struggle with the complicated ideas of race and identity. The difference between my daughter’s official race, my own self-identification as “American,” and my birth certificate record as “negro” demonstrates how fluid and subjective racial categories are. I am a citizen of the United States of America. Although I identify as an American, my ancestors were African. I know this because my cousin Sharon Thompson Solari undertook family genealogical research and determined that our ancestors originated in Africa and immigrated to the United States via a Virginia slave ship. This does not, however, classify me as an African American. I am a citizen of the United States of America.

As our history demonstrates, this inclination can lead to widespread discrimination. Among them are Americans of foreign ancestry. Italian Americans, Chinese Americans, Irish Americans, Native Americans, and Japanese Americans, to name a few, have faced significant discrimination as a result of their classification, labeling, and titling. For instance, World War II discriminated against Italian Americans, interning them as enemy aliens despite their American citizenship. Similarly, Chinese Americans faced discrimination with the late 19th century implementation of the Chinese Exclusion Act, restricting their immigration and naturalization rights. These atrocities serve as a stark reminder of the dangers of unchecked prejudice and discrimination. The internment of Japanese Americans and the persecution of Chinese immigrants highlight the importance of upholding the rights and dignity of all individuals, regardless of their race or ethnicity. We must draw lessons from these dark chapters in history to prevent the recurrence of such injustices. Internment camps imprisoned Japanese Americans without due process, treating them like Holocaust victims as they struggled to maintain their American title. Internment camps were a precursor to the horrors of the Holocaust in Europe in the late 1930s, as fascism decimated the ranks of many “good people.”

Both camps had a racial component in their target population, which makes them more similar than most would care to admit. The United States government stripped them of their “American” title, reducing them to simply “Japanese.” During World War II, the U.S. government suspended their right to due process through Executive Order 9066, authorizing the relocation and internment of Japanese Americans deemed a threat to the war effort (Japanese Americans at Manzanar). As a result, the U.S. government established internment camps like the Manzanar War Relocation Center, imprisoning Japanese Americans against their will. (Japanese Americans at Manzanar.). Despite upholding the evacuation’s constitutionality based on national ancestry, the Supreme Court ruled that detaining loyal citizens involuntarily was not permissible (Japanese Americans at Manzanar). The Walter-McCarran Immigration and Naturalization Act allowed Japanese aliens to become naturalized citizens after the war ended in 1945 (Japanese Americans at Manzanar). In 1988, the U.S. Civil Liberties Act awarded compensation and an apology to former internees (Japanese Americans at Manzanar).

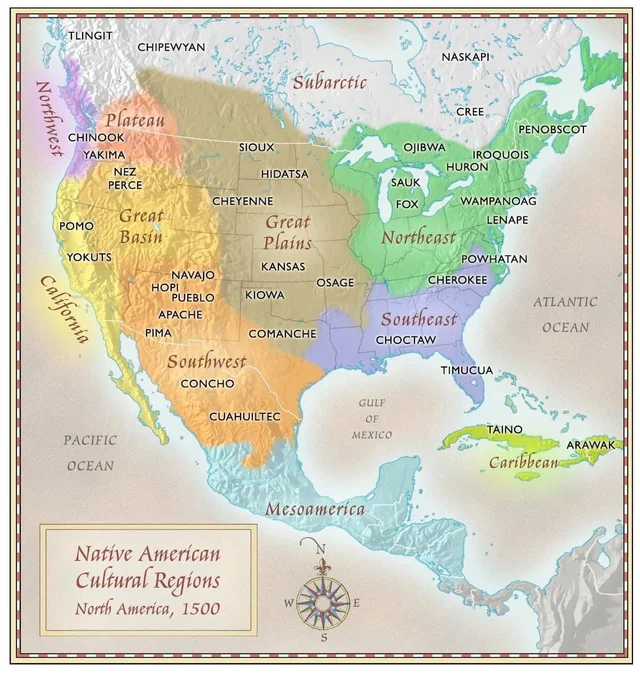

This discrimination has had lasting effects on these communities, shaping their experiences and opportunities in American society. Despite these challenges, many individuals from these backgrounds have made significant contributions to the country. One day, I hope people will simply refer to me as an American, as I am. I believe that recognizing and respecting each individual’s unique heritage is essential to fostering a more inclusive society. We can progress towards a future where we view all Americans as equals, irrespective of their ancestry, by embracing diversity and comprehending the complexities of identity. If one thinks deeply enough, the only truly American people are those who came before Europeans, such as indigenous Americans who lost their country and received the titles Native Americans and Indians.

They are the true Americans, as they have a connection to the land that predates any other group. Recognizing and honoring their heritage is essential to understanding the complex history of America.

It is difficult to accept that “good people” participated in the process that allowed settlers and capitalists to profit from vast mineral deposits such as gold and silver, land acquisitions, and ultimately the petroleum rights of dispossessed Indian tribes and territories. (Native Nations Face the Loss of Land and Traditions) While these individuals may have viewed their actions as justified or necessary for progress, the lasting impacts on indigenous communities cannot be ignored. The exploitation and displacement of Native American peoples for the financial gain of others highlights the inherent injustices and inequalities embedded in our nation’s history. It is crucial to acknowledge and reckon with this dark chapter in order to work towards a more equitable and just future for all. One example of this exploitation can be seen in the California Gold Rush, where settlers forcibly removed Native Americans from their lands in search of gold, leading to mass displacement and violence. Additionally, the Dawes Act of 1887 allowed for the allotment and sale of Native American reservation land to non-Indigenous individuals, further eroding tribal sovereignty and cultural integrity.

According to Wikipedia, more than 500 treaties between the United States government and Indian tribes have been broken, amended, or nullified. The treaties were often broken or coerced, and many were based on complex issues with the goal of taking land from the tribes by force. For example, between 1851 and 1852, 18 treaties were signed with 122 California Native American tribes. (List of United States Treaties - Wikipedia, 2024)

1638 – Treaty of Hartford to 1868 – Treaty of Fort Laramie – with the Sioux and Arapaho ending Red Cloud’s War.

(List of United States Treaties – Wikipedia, 2024)

It’s ironic that I had to travel to foreign lands shaped by colonialism in order to feel normal and communicate on a level that I could never find in America. I feel more at ease in places where I don’t speak the language, but I find communication through gestures and broken Spanish, Hangul, or Tagalog to be incredibly rewarding, comfortable, and unique. I feel more at home, more alive, and more like myself. Exploring diverse cultures and languages allows me to step out of my comfort zone and truly connect with others in a meaningful way. It’s a reminder that there is beauty in diversity, and that true communication goes beyond just words. It opens my mind to new perspectives and ways of thinking, enriching my understanding of the world around me. Traveling the world has given me a sense of belonging and a deeper appreciation for the richness of human connection.

W. E. B. DuBois talked about “double consciousness” as an important part of the African American experience. It is becoming clearer that the way each person mixes their African and American awareness is different. Richard Wright says: “The recipe for mixing our African with our American consciousness varies with each individual.” Wright stated that as people of African descent, we run the risk of only acting black instead of exploring the infinite ways our real experience and creative imagination can be shaped as black people and as true Americans. Our desire to embody or represent real black identity may make our cultural heritage less rich and our historical experience less complicated. (Young) When African Americans don’t accept each other’s differences, bad things often happen, like in the Spike Lee movie “Bamboozled.” Wright says that “Negro literature” is still around because of slavery and racism in the US. In his speech, he says that the harshness of the U.S. past changes how black creativity is. James Joyce called it “the uncreated conscience of a race.” Wright emphasizes the impact of historical trauma on African American creativity, highlighting the lasting effects of slavery and racism.

This perspective sheds light on the complexities of black identity and cultural heritage in America. (Young) I believe that the lesson I have learned is that “choice,” or having the ability to make a choice, is a powerful weapon of democracy. By recognizing the impact of historical trauma on creativity and identity, we can work towards dismantling systemic barriers and promoting equality. Understanding the power of choice in democracy allows for progress and empowerment in marginalized communities. What makes us all human is our relationship with that only factor that does not divide us—our mortality and our shared ethos: nevermore. We all deal with things that will be no more, people that we knew that are never more, and family that we know will be never more. My race needs no special defense, for the past history of them in this country proves them to be equal to any people anywhere. All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life.